- Home

- Nathan Hawke

The Crimson Shield Page 17

The Crimson Shield Read online

Page 17

The fissure widened, spilling them out into a slanting cave that ran deep to the bottom of the rauk. He could smell the seawater at the bottom, rank and salty. The Lhosir torches barely touched the darkness of it, but it was easy to see where the cave ended and the water began because that was where the monks of Luonatta were waiting for them, fifty feet below. They stood in a circle on a tiny island surrounded by rings and rings of candles and black glittering water. A narrow wooden stair, steep and creaking, wound down the side of the rift, little more than a string of wooden pegs hammered into holes in the rock. Now and then, as Gallow shifted his weight from one to the next, he felt them flex and bend, heard them creak. There was nothing to hold on to except the damp wall of stone, pressed so close beside him that it seemed to want to push him over, down into the depths below.

As the Lhosir entered the cave the monks began chanting. Something lay in the middle of their circle, large and round. The cave was too dark to make out what it was, but there was only one thing it could be: the shield. Gallow shook his head. Monks were the same everywhere – he’d seen it enough times among the Marroc. When terror came to call they made a circle and prayed to their gods, and from when he’d followed the Screambreaker he couldn’t think of a single time those prayers had been answered. What were they praying for? That Medrin and all his men would slip on the narrow steps and break their necks? Lhosir didn’t pray. The best they could hope for was for the Maker-Devourer to ignore them. The closest thing the Lhosir had to people like these monks were the iron devils of the Fateguard, the soldiers of the Eyes of Time, and they certainly wouldn’t meekly close their eyes and pray and die.

A man swore behind him and then another screamed as he slipped and plunged into the darkness below. Gallow didn’t dare turn to look. A deep unease washed over him here in this dark place under the earth with strange men and their strange gods waiting for him. Maybe there was something to those prayers after all. Prayers to what?

The steps brought him down to a shelf of rock almost level with the water and slippery with black seaweed. A small wooden bridge led to the island. After the crudeness of the steps, it was strangely ornate, narrow but with a rail on either side and carved with fish-like figures. Water monsters. Serpents. Women who were half beast. The other men stopped behind him, waiting, none of them sure what to do until Medrin pushed past them all and came to stand beside Gallow at the bridge.

‘Hey there!’ He waved his sword across the narrow waters. ‘We’ve come for your shield. It belongs to the Marroc. If you’d be so kind as to pass it over, we can be on our way. I also have some swords here that you can fall on, if you’re feeling accommodating.’ The shadows of the flickering torchlight had changed his face. He looked somehow monstrous. Eyes agleam, teeth bared in a hungry grimace.

The monks didn’t even look at him. Their faces were glassy, chanting the same words over and over: Modris, Modris, Protector! Modris, Modris, Builder! Modris, Modris, Maker! Modris Modris . . .

Modris? Gallow started as though he’d been stung. Wasn’t this supposed to be a temple to Luonatta the battle god? Why were the monks chanting the name of Modris?

‘Oh never mind.’ Medrin stepped back from the bridge. ‘Gallow, since you were clever enough to get us through the gates, I give you the honour. Kill them for me.’

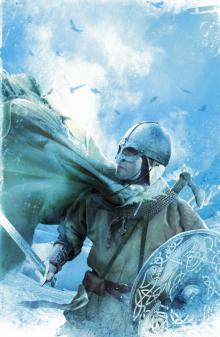

Gallow’s feet wouldn’t move at first. He touched the locket around his neck and felt it urge him to turn and leave and go home and never look back. There was something wrong with this place; but maybe that was only his old Lhosir blood and all its wariness of what lurked in the deeper places of the world where the shadewalkers were born. And then his Lhosir pride had him too, refusing to let him show his fear, and so he stepped onto the bridge, tense as a drawn knife. When nothing happened he began to walk across. His hand felt tight on the hilt of his sword, restless and twitchy, screaming at him for release. He pushed the hunger aside and merely shoved the first two monks out of his way and pushed them into the water. The others didn’t move. He reached for the shield. His arm tingled as he did and his heart beat a little faster. A dozen years ago Medrin and Beyard had been transfixed by this god-forged shield and what it meant, and he’d been no better. Now he told himself what the Screambreaker had told him after he’d crossed the sea and found the courage to ask: it was just a shield and nothing more, one that happened to be red. And yet the hairs on his arm prickled as he touched it. The Crimson Shield. The invincible shield of Modris the Protector.

Not that it had saved the Marroc. Just a shield, that’s all.

He pushed another monk away, set his own shield down and took the Crimson Shield instead. It was heavy. Instinct demanded that he put it on his arm but that would be to claim it for himself, so he carried it carefully back across the bridge, hairs still prickling all over his skin. The monks continued their chanting as though nothing had happened. Even the ones he’d pushed into the sea were climbing back out of the water, shaking their robes and retaking their places back in the circle. Gallow took a long look at the shield as he held it out in front of him. The darkness and the torchlight hid its colour. It looked like a simple round shield, thick wood reinforced and studded with metal. A single colour, dark grey in the cave but surely crimson in the sunlight. No design. He offered it up to Medrin. ‘Here you go then.’

‘Funny,’ said the prince as he took it, ‘to hold it after all these years. Don’t you think?’

‘It’s just a shield.’ Gallow let it go. His fingers didn’t believe him and his guts didn’t either, but how could it be anything else?

‘You seem to have left yours behind.’

‘That was some islander piece of rot. I left mine back on the cliff.’ He shrugged and walked away.

‘Gallow!’ Medrin called him back.

‘Twelvefingers?’

‘I told you to kill them.’

‘And I didn’t. I got you the shield. That’s what you wanted.’

‘No, I wanted you to kill these thieves who took what was ours and claimed it for themselves.’

‘King Tane’s heir are you now?’

‘My father is king of the Marroc.’

‘Then kill them yourself. There’s no honour in slaughter.’ Where was Jyrdas when he was needed? Even bloodthirsty old One-Eye would say the same.

‘There’s honour in serving your prince, clean-skin.’

‘Then I’m sure you’ll find someone to do it for you.’

Medrin looked past Gallow to the other men. ‘A village full of Marroc to whoever kills a monk. Go. Have yourselves some fun.’

No one moved, not straight away. ‘Lord of a village full of sheep?’ called a voice from the back. ‘What would I do with them?’ Tolvis. Damn it, where was Jyrdas?

‘Probably something unnatural, Loudmouth.’ The big man Horsan stepped forward, gripping his giant axe. Gorrin, the archer with the broken arm, pushed his way to the bridge too.

‘If I kill two, do I get two?’

‘Kill six, you get six,’ said Medrin with a shrug, and with that half the Lhosir swarmed over the bridge, howling and swinging their swords. The other half stood and looked at one another, muttering uneasily. It was over in a moment and then the Lhosir fell silent and stopped to look at what they’d done: a dozen unarmed monks crumpled in a ring around the stone where the shield had been. A dark tension swirled around them.

‘I don’t know about the rest of you,’ said Tolvis from the back, ‘but I think I’ve had about enough of this place. I think I shall be off a-looking to see if these monks had themselves a wine cellar anywhere. Those who fancy a swill, Gallow, are very welcome to join me.’

Tolvis began to climb the steps. He wasn’t the only one, but in the gloom Gallow couldn’t see who else went with him. And he ought to go too, he knew it, but he couldn’t quite bring himself to move. Medrin ignored them all. ‘It’s called what it’s called for a reason,’ he said, and he walked across the bridge and put the shield back where Gallow had found it. He knelt beside a de

ad monk and began to cut out the man’s heart.

‘No.’ Gallow pushed his way back towards Medrin. ‘No, Medrin, we do not do this.’

‘Stop him.’ Medrin didn’t look up. ‘Kill him if you have to.’

Twelvefingers took out a knife, felt for the bottom of the dead man’s ribs, then drove the blade in deep and slit the monk open. He reached in, struggling for a moment before he tore out the dead monk’s heart, bloody strands of flesh trailing behind it, and squeezed it over the shield. Gallow drew his sword. Three men seized him. He tried to shake them off. ‘Blood rites, Medrin!’

‘Let it go, Gallow,’ warned Horsan. ‘There’s no good end to this. Our prince knows what he’s doing.’ He didn’t even seem surprised.

Gallow broke free and readied his sword again. He surged towards the bridge, the other Lhosir moving uncertainly out of his path. ‘Innocent blood, Medrin!’

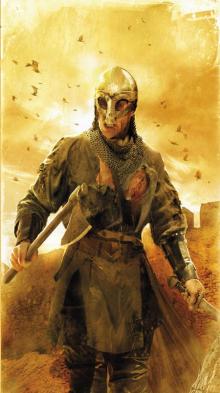

‘Innocent?’ Medrin lifted the shield and held it high. ‘These monks?’ he cried. ‘Innocent? Maker-Devourer, they’re dead! And maybe these monks were innocent, but what of all the Marroc that you and the Screambreaker and all the rest put to the sword?’ He bared his teeth. ‘You’ve forgotten what you are, Gallow. You’re no nioingr but you’re no Lhosir either. You’re nothing but a Marroc like any other.’ He kicked the nearest dead monk, slapped the iron rim of the shield down on the stone and pointed at Gallow with his sword. ‘You have no idea what this is, no-beard. You have no idea what it can do, what it means. If you did, you wouldn’t ride your sanctimony so sweetly. A little ritual of thanks to the Maker-Devourer and you draw steel on me? You forget where this came from and you forget what you are! Yes, Gorrin, please.’

Gallow blinked, realised that Medrin was no longer looking at him but past him instead, and that was when someone hit him round the back of the head with the butt of an axe.

Light and noise and then quiet and dark. He was standing on a hilltop in the twilight, a steady wind blowing around him. He knew the place at once. His old home, where he’d grown up before his father had taken them to Yurlak’s Nardjas to make armour for the Screambreaker. He remembered the hill. A favourite place, especially when the sun was setting. He used to go there with Kyerla, the sweetheart of his childhood. He hadn’t thought about Kyerla in ten years, but he remembered now how much he’d missed her when his father had taken them away. In a different world, one where they’d stayed in their forge and their farm by the sea, he and Kyerla would have been married, younger even than when Gallow had crossed the sea. He could be there now, curled up with her softness under a pile of furs with six or seven fine sons . . .

He sensed movement and turned, expecting to see her, but the woman waiting for him was Arda, arms outstretched. ‘Remember us, Gallow.’ He couldn’t see his children, but they were there too. He felt them. Kyerla was forgotten as quickly as she’d filled him. He tried to walk towards Arda but something caught his eye to make him look away. When he looked back she was gone and all he saw standing at the top of the hill was a long sword, dark red, stuck fast, point down in the chalky earth.

‘No, don’t kill him . . .’ Words drifted in and out. Light flickered and came and went.

‘We could just leave him.’

‘Any of you want a fight about it?’

‘What about him?’ The pain was huge. Even blinking hurt.

‘One-Eye?’ The back of his head. ‘Is he still alive then?’ He couldn’t touch it. His hands were tied. When he moved he felt a sharp tug on the skin at the back of his neck. Dried blood.

‘He’s made of granite, that one. He’s bound to live.’ His blood.

‘Bring them both.’ Deep breaths. Fighting back the waves of nausea. ‘The dead too.’ One after the other. ‘Put a torch to the rest.’ Too much effort. His eyes wanted to close again. To let it all pass.

Another voice, hurried. ‘Get back to the ships!’ He forced his eyes open. Took deep breaths, one after the other. He slipped in and out of darkness a while, but by the time the Lhosir were ready to leave, his senses were back enough that he could stand. His hands were tied behind his back. Gorrin and two men who’d sailed with Medrin were standing guard. A few bodies lay around him. Off across the yard Tolvis was shouting at someone about an axe. He had Jyrdas slumped against him, leaning hard on his shoulder. The big man looked ready to collapse.

They’d taken his weapons. The worst humiliation. ‘Gorrin!’ It had to have been the archer. ‘You hit me. You took me from behind.’

Gorrin gave him a look of disdain. ‘You were heading sword drawn towards our prince, Marroc.’

‘A good blow for a man with a broken arm, I’ll give you that. You don’t need me to say what sort of man takes another from behind. You know the answer.’

Gorrin leaned into him. ‘When I have my arm back, Marroc, I’ll be happy to talk about the answer to all sorts of things. Prince Twelvefingers killed a few monks? So? You’re on your own if you think anyone gives a pot of piss about that.’

Medrin got them back on the move quickly. The Lhosir were surly now. The fighting was done, the battle madness sated, the fires were lit and buildings blazed all around them. They had little to show for their fight; they were hungry and tired and they wanted to go to sleep, and now Twelvefingers was going to make them walk back across the cliffs to the ships in the dark and row out to sea. Gorrin turned to Gallow. ‘If the soldiers from that castle catch us out in the open, I’ll cut you free, but only for that.’

The moon had sunk below the horizon. Clouds hid half the stars, making every stone and every divot a hazard in the dark. They stumbled across the fields and cliff-tops in moody silence, carrying what they could, shields thrown over their backs, plunder on their shoulders, the fires of the burning monastery lighting their way. Medrin would expect them to sail as soon as they reached the ships and work the oars until the morning. As far as Gallow could see, the monks of Luonatta had hardly been rich. The spoils were meagre. A few barrels and casks stolen from the pantry but no gold, no treasures, no women, nothing worth taking home, nothing even making it worth leaving Andhun in the first place except for the Crimson Shield.

Tolvis and Gallow took turns to prop up Jyrdas. They reached the beach. No one had burned their ships, and before dawn broke the sky they were riding the sea again. A melancholy settled around them despite their victory. A sadness for the men who were dead and an uneasy sense of something changed and thus something lost. Maybe on the other ship, with Medrin and with the Crimson Shield there for all to see, things were different, but on the second boat Gallow thought he felt a creeping edge of doubt. Jyrdas hobbled around, screaming murder at anyone in his way, face screwed up in permanent pain. Wind and wave fought against them as if trying to turn them back, making them slow. With the madness of the fight cleared from their heads, the Lhosir around him remembered what they and Medrin had done. Gallow made sure to remind them.

They kept him bound, tied to the mast through wind and rain even when they could have used another strong pair of arms on the oars. ‘I can row,’ he told them. ‘Where am I going to go?’ He saw them waver but that was all. Even Jyrdas looked at him with a face full of rage. Maybe they were afraid he’d throw them all over the side and sail to Andhun single-handed.

On their third day at sea a storm hit. They took in water and almost foundered. Oars broke, snapped by the strength of the waves. The Marroc in Gallow would have said it was a miracle they didn’t sink and drown, but Lhosir didn’t believe in miracles. Fate, perhaps, had spared them, or perhaps they were merely lucky: Jyrdas and the others who’d been to sea before certainly thought so. When the winds passed and the waves fell, they lay about the deck and slept and broke open a cask of mead taken from the monastery and drank toasts to the Maker-Devourer, and Gallow thought nothing of it until Tivik, who might have been the youngest of them, raised a drunken horn to the clouds.

‘To Medrin! It was the Crimson Shield that guided us! The shield of the Protector!’

Jyrdas, on another day,

might have thrown Tivik into the sea for being an idiot, but Jyrdas was fast asleep and half dead. The other Lhosir gave Tivik queer looks and muttered to themselves, but he wasn’t alone. It spread among them like some disease, slow but lethal.

‘It’s just a shield,’ Gallow tried to tell them, but by the time they reached Andhun none of them wanted to know.

29

THE MARROC

After the storm, the wind and the waves favoured them to Andhun. The castle still sat on the cliffs overlooking the harbour. Teenar’s Bridge still lay strung across the Isset. Nothing, as far as Gallow could see, had burned down, although the blood ravens hung across the docks had been cut down and the gibbets were gone. The town felt quiet and peaceful. The Vathen, then, hadn’t yet come.

The Lhosir made good their ships and unloaded what was left of their plunder from the monastery. Their melancholy had gone after the storm, replaced by a strange fervour for the shield. They bound Gallow and manhandled him to the shore and then when they were standing on the beach together, they crowded Medrin, trying to see the shield more closely. Touching it. And yes, in the light of the day it was as crimson as fresh blood, and either Medrin had spent a great deal of time cleaning and polishing it, or perhaps it did have a magic to it after all.

The shield took their eyes, and that was why they didn’t see the Marroc at first. Not too many, just a dozen men gradually gathering together, keeping their distance but watching from the top of the shingle beach with the air of those waiting for something to happen. As Gallow eyed them they were joined by more, and then more still, until the first dozen had become two and more were coming all the time. He saw Valaric among them, and was that Sarvic too?

Cold Redemption

Cold Redemption The Last Bastion

The Last Bastion The Crimson Shield

The Crimson Shield